Our eyes are incredibly versatile in detecting various levels of light. And while no one can see in complete darkness, it is amazing how little light is needed for our eyes to find their focus.

The eye’s natural adjustment to the various lighting conditions is known as adaptation, and it is performed by three of the eye’s key structures– the iris, retina, and pupil.

From bright afternoon sunshine to near-total darkness, find out how your eyes adapt to the types of lighting situations we encounter every day.

How eyes adaptation works

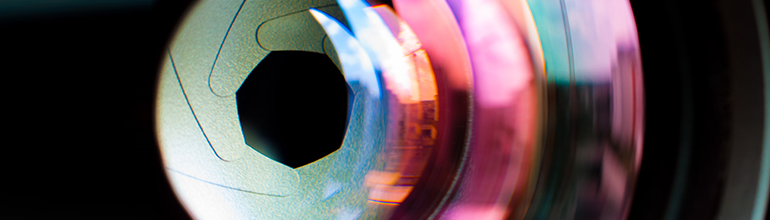

If you have ever used a traditional point-and-shoot camera, you might be familiar with the term – aperture. The adjustable lens opening allows light to pass through so the camera can focus on an image. The human eye works in a remarkably similar fashion.

While the iris structure is known for providing the colour or pigment of the eyes, it is also made up of miniature muscles that work in tandem with your pupils. As the gatekeepers, these two regulate the right amount of light entering the eye. The pupil behaves in the same way as the adjustable camera aperture as mentioned above.

In dim lighting, the muscles relax, allowing the pupil to dilate allowing more light to enter. In bright environments, the muscles contract causing the pupil to constrict, minimising the amount of light needed to focus.

Once the light enters the eye through the circular pupil, it is filtered through the retina onto light-sensing cells that line the back part of the eye called photoreceptors. These are divided into two groups according to their shape and function:

- Rods: responsible for nighttime vision, has a low resolution but is more abundant.

- Cones: contribute to daytime vision, are responsible for colour vision and are fewer in number.

Combining these two cell receptors’ functions allows our eyes to adapt to various lighting conditions–with the retina switching the workload between the rods and cones based on the amount of light that the pupils let in.

How your eyes adjust to the dark

If you have wondered how it is possible to see in a dark room with little to no light, you have your rod photoreceptors to thank. When the lights turn off, you might notice it takes a little time for your vision to adjust. That is because these rod receptors are “bleached out” from the light source that was just shut off, and it takes time for them to regenerate their rhodopsin pigments.

This process, called dark adaptation, happens at slower rates than its opposite (light adaptation)– because our rod receptors are more sensitive and 15x more plentiful than their counterpart cone cells. During this period of rhodopsin restoration (which sometimes lasts up to an hour), our pupils dilate as wide as possible to let in any available light sources that will improve our vision in the dark.

How your eyes adjust to bright light

After a film, have you ever stepped out of a dark cinema into the shining afternoon sun? If you have, then you are familiar with the glare that momentarily shocks your eyes into blinking as they begin to adjust to the brightness.

This influx of light sends a wave of stimuli to our pupils and photoreceptors to begin the process of light adaptation. Like dark adaptation, this automatic adjustment takes place in the back of the retina with our rod and cone receptors. However, since cone receptors are more agile than rods and fewer in number, their response time to instant lighting changes is quicker. Cone cells regenerate about 5x faster than rods which allows your vision to rebound to normal in less time.

What is light sensitivity?

Instant changes in light can lead to light sensitivity in some people. Also known as photophobia, this issue occurs when bright lights cause discomfort to your eyes. For some, that can extend to headaches, nausea, and trouble readjusting to their normal vision after experiencing overly glaring light.

While photophobia can affect people of all ages, it is more common with people that have lighter coloured eyes, ageing eyes, and sometimes as a side effect of certain medications. Light sensitivity is a symptom of another problem, not a condition on its own. And it can be triggered alongside some of these conditions.

Causes of light sensitivity (photophobia):

- Migraines

- Facial pain (dental, meningitis, nerve disease)

- Dry eyes

- Light-coloured eyes

- Albinism

- Dilated pupil

- Corneal scratches / retinal detachment

- Eye infections/inflammation

- Cataracts

- Glaucoma

- Drugs (both recreational and prescription)

- Wearing contact lenses incorrectly or too long

- Photokeratitis (sunburned eyes)

What to do if you are experiencing light sensitivity

Because light sensitivity usually occurs in conjunction with another issue. The best way to deal with it is to identify the underlying cause. In most cases, light sensitivity disappears once the triggering effect is treated.

For those inherently sensitive to bright light or have lighter toned eyes. Follow the regularly advised outdoor safety precautions against harsh sunlight with hats and UV protective sunglasses.

If you notice that you are experiencing photophobia after starting a new medication regime, consult with your GP about alternative drug options.

In all instances, if light sensitivity is affecting you on a continuous basis, is severe or painful, or occurs even in low-light conditions–contact a medical professional for advice.